About The Treaty Map

The Map depicts three eras of treaty-making: Pre-Confederation (1763-1867), Confederation-Era (1867-1921), and so-called “Modern” Treaties (1975-Present). It also includes descriptions of the era of Indigenous diplomacy and an overview of non-treaty lands. The Treaty Map is a comprehensive overview of treaty in Canada.

ABOUT THE TREATY ERAS, INDIGENOUS DIPLOMACY & NON-TREATY LANDS

Pre-confederation treaties are those negotiated from 1763, the date of King George III’s treaty-making Royal Proclamation to 1862, just before Canadian Confederation. The treaties captured in this era represent early English attempts to establish sovereignty, and obtain land for settlement and colonization. They were considered transactions, above all else. From a First Nation perspective, however, these agreements served to solidify a post-war alliance and represented peace, friendship, and sharing agreements. These early colonial treaties, sometimes called the “blank” treaties, often lacked documentation, were negotiated very quickly, and were plagued by confusion and obfuscation. It is no surprise, then, that nearly all of the pre-confederation era treaties were — or continue to be — contested in litigation and negotiation. The treaties in this era are a record of Canada’s attempt to dispossess Indigenous people from the land and assert sovereignty via deception and fraud.

The Confederation era treaties – often simply referred to as the “Numbered Treaties” – are those negotiated from 1871 to 1923. After 100 years of pre-confederation era treaty negotiations, First Nations North and West of the Great Lakes began demanding clearer terms in treaties, so Canada applied a strategy of standardization. They sought land surrender and relocation to make way for settlement, paired with modest services, annuities and occasionally support for a transition to European-style agriculture. For their part, First Nations continued to exercise their view of treaties as sharing agreements that reflected shared sovereignty and relationality. In most First Nation accounts of these treaties, settlers were simply obtaining access to land “no deeper than the depth of a plow” with limited impact on their day-to-day lives. But when these competing visions of treaties resulted in conflict, the Indian Act was deployed to coerce First Nations to abide by the Crown’s interpretation of terms. The fight for a just interpretation of the Numbered Treaties endures.

The so-called Modern Treaty era began in 1975 and continues into the present. Following the conclusion of the Numbered treaties in 1923, Canada abandoned treaty-making. But First Nations, Inuit and Métis protested the illegal occupation of their land and exploitation of their resources in Quebec, the West and the North. This unfolded in the courts with the Calder Decision, resistance to the 1969 White Paper, and the MacKenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry. Paired with Canada and the territories’ rush to develop hydroelectric and oil and gas resources, a new land claim process emerged, resulting in modern treaties. While treaties in this latest era are more comprehensive in scope, access to the land remained the overarching goal for Canada. In exchange for extinguishing, modifying, or not asserting title to the vast majority of their territories, First Nation, Métis and Inuit in the modern treaty era secured financial compensation, consultative rights, and options to negotiate self-government. The challenge, as with previous eras, is their lack of implementation.

Indigenous diplomacy and treaty-making pre-dated Canada and has been practiced before and during Pre-Confederation, Confederation and even Modern Treaty eras. This diplomacy draws on Indigenous legal traditions, from each part of the country, and is embedded in creation narratives, social organization, governance protocols and formalized negotiation with other Indigenous people and with settlers. It has sought to enshrine principles of mutual autonomy, shared sovereignty and relationality as well as the agency of the land and reciprocity. As Canadian treaty-making practices came to dominate the relationship, Indigenous diplomacy nonetheless endured, challenging unilateral assertions of sovereignty and the commodification of the land. This resistance has formed the basis of arguments against concepts of land surrender or treaties as transactions and continues to drive contemporary Indigenous interpretations of treaties as well as the creation of new Indigenous-led treaties.

In some parts of the country, no treaties exist. This is predominantly so in the province of British Columbia but also the case in regions of the North, Quebec and the Maritimes. There are a variety of reasons for this lack of treaties, from Canada’s presumption that no Indigenous peoples occupied the land, to exceptionally long-delays in negotiation, or First Nations deciding that the treaty process does not reflect their interests. Canada’s insistence on concepts of surrender, in particular, has pushed communities in these regions to practice alternative forms of diplomacy. These range from unilateral assertions of rights and title, court declarations, and, in some cases, sectoral agreements that set out rights and responsibilities for all parties for a specific time period. Given the implementation challenges of modern treaties, these evolving “reconciliation” agreements in non-treaty title lands may become the next era of Canadian treaty making. But, until it is widely practiced – if ever – it is important to note that in these regions, Canadians occupy the land without the consent or agreement of Indigenous people.

METHODS & LIMITATIONS

Treaties are contentious. They are frequently the subject of court cases, land claims, re-interpretation and re-negotiation. There are a variety of perspectives, nuances and very real boundary disputes that accompany each treaty, and we recognize that The Treaty Map does not capture it all. In this sense, The Treaty Map is an introduction to treaty history in Canada.

If you would like to share feedback or edits to Treaty Map, please fill out the form on our FAQ page.

Each treaty entry has been researched to centre Indigenous perspectives on the context, those involved in the negotiations, the terms—often with multiple interpretations—and the events that followed the negotiation (or implementation of the treaty). Each entry is 250–300 words and written in plain language. The research draws on a variety of sources, all of which can be found here. After the initial research, drafting, and editing were completed, advisory committees composed of Indigenous treaty experts offered advice that strengthened the content.

There are limitations to the research. Primary and secondary sources overwhelmingly centre non-Indigenous, male perspectives on treaties. While we have sought to retrieve a greater diversity of material, this has only been partially successful. It is the hope that Indigenous scholars working on treaties continue to challenge dominant narratives and re-articulate Indigenous — especially Indigenous women and queer — perspectives. We will update The Treaty Map as those resources become available.

This map is largely about Canadian treaty-making practices; the three eras represented here all centre important eras in the country’s history (e.g. the Royal Proclamation, Confederation, etc.). But there are many treaties that do not fit within these categories. We have included some notable pre-1763 treaties but the period between 1701 and 1763 is largely unaccounted for. Meanwhile, we have included Metis diplomacy only marginally. In both cases, the current available research that includes Indigenous perspectives here is limited.

While interactive, the Treaty Map is also a “traditional” map in that it reduces treaties to a two-dimensional graphic representation, limiting the relational and cultural elements of the agreements and depicting the landscape as static. The boundary coordinates for each treaty shape were drawn from existing publicly available data sets and cross-referenced to produce the map. As noted in some of the treaty entries, the boundaries themselves are the subject of ongoing dispute, may not reflect agreed upon terms, and affirm colonial boundaries generally.

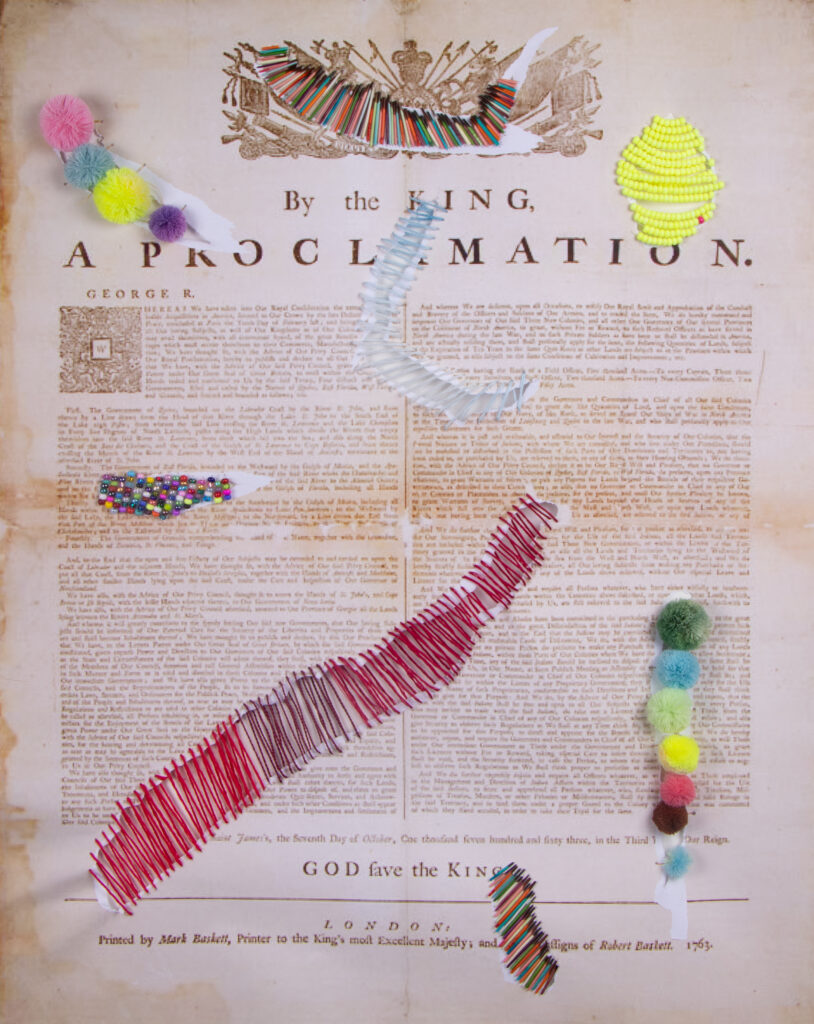

Proclamation, 2023

Inkjet print, embroidery, porcupine quillwork, seed beads, caribou hair tufting;

Framed: 26.75 x 21.75 x 2.25

ABOUT THE ARTWORK

The Treaty Map site features the art piece Proclamation by Michelle Sound, licensed by Yellowhead Institute. The Indigenous Treaty Making Era map layer also features artwork by Michelle Sound.

Artist Statement on Proclamation

An image of the Royal Proclamation of 1763 is ripped, demonstrating the colonial violence that the Crown and governments have inflicted on Indigenous people. While the Royal Proclamation recognizes Indigenous rights and title in so-called Canada and encourages the signing of nation-to-nation treaties, it was written without input from Indigenous people and was not created for our benefit. The ripped image represents the damage that colonial laws and broken treaties have caused, including our ability to fully access our territories and communities. The rips in the document are mended with beadwork, caribou tufting, and porcupine quills, showing the survival of our ancestors, our stories, and our culture. Indigenous people continue to assert our sovereignty and connection to the land regardless of government legislation. Save The Kin.

About the Artist

Michelle Sound is a Cree and Métis artist and mother. She is a member of Wapsewsipi Swan River First Nation in Treaty 8 Territory, Northern Alberta, and she was born and raised on the unceded and ancestral home territories of the xʷməθkwəy̓əm (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish) and Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations. Sound’s work explores personal and familial narratives with a consideration of Indigenous artistic processes. Her works explore cultural identities and histories by engaging materials and concepts within a contemporary context.